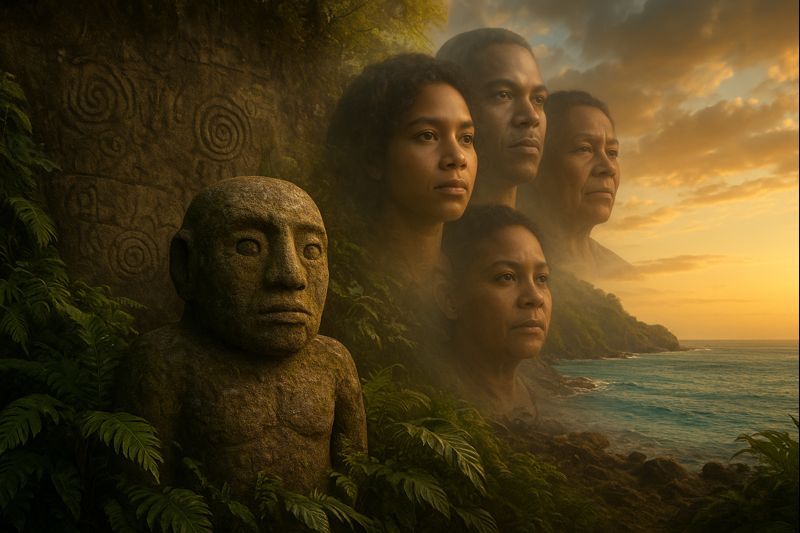

When geneticist Juan Martínez Cruzado announced his findings in 2003, he expected surprise. What he didn’t anticipate was the tears. Sixty-one per cent of Puerto Ricans, his research revealed, carry Taíno mitochondrial DNA—the genetic signature passed exclusively through maternal lines. For two centuries, history books had declared these indigenous Caribbean people extinct, bureaucratically erased from an 1802 census that conveniently listed zero “pure” Indios where thousands had existed just fifteen years prior. Yet here was scientific proof that the Taíno had never truly vanished. They had simply become invisible.

This is the paradox at the heart of Caribbean identity: a genocide so thorough that it convinced the world entire civilisations had disappeared, and a survival so resilient that millions of their descendants walk the earth today, largely unaware of the indigenous blood coursing through their veins.

The Sophisticated World Before

Long before European sails appeared on the horizon, the Caribbean archipelago thrived with complex societies that contemporary accounts routinely diminish as “primitive.” The Taíno people—part of the broader Arawakan linguistic family that had migrated northward from South America’s Orinoco Delta around 400 BCE—had transformed the Greater Antilles into a network of agriculturally sophisticated settlements. Conservative estimates suggest between one and two million people inhabited Cuba, Jamaica, Hispaniola, Puerto Rico, and the Bahamas when Christopher Columbus arrived in 1492.

These were not simple hunter-gatherers scratching subsistence from tropical soil. Taíno society organised itself into hierarchical chiefdoms led by caciques, with power passing through matrilineal inheritance—a system that afforded women considerable authority in a world Europeans would later describe as universally patriarchal. Villages of three to five thousand people practised conuco agriculture, an ingenious raised-bed farming technique that prevented soil erosion whilst maximising yields of yuca, maize, beans, and sweet potatoes. They worshipped zemís—spirits embodied in intricately carved representations—and built ceremonial ball courts that doubled as social centres.

Further south, the Kalinago people dominated the Lesser Antilles, including Dominica, parts of Guadeloupe, and Martinique. Spanish colonisers branded them “Caribs”—from which the word “cannibal” derives—in narratives designed to justify violence through dehumanisation. Modern scholarship reveals these accounts as largely propaganda. The Kalinago were formidable seafarers, yes, but their society was equally matrilineal and comparably complex, with clan structures that regulated everything from marriage to territorial disputes.

The linguistic legacy alone testifies to their sophistication. Every time we speak of canoes, hammocks, barbecues, tobacco, or hurricanes, we invoke Taíno words that proved so perfectly descriptive they survived the language’s near-extinction. More than three hundred herbal medicine terms persist in Puerto Rican Spanish, passed down through generations of healers who maintained indigenous botanical knowledge even as they were forced to practice it in secrecy.

The Great Dying: When Numbers Tell Stories Words Cannot

Columbus’s initial observations of the Taíno drip with paternalistic admiration: “well-proportioned,” “trustworthy,” “very liberal with everything they have.” Within a generation, these same people would face what Yale University’s Genocide Studies Program now classifies as systematic extermination. The demographic collapse was so swift and comprehensive that it challenges comprehension.

On Hispaniola—the island now divided between Haiti and the Dominican Republic—the Taíno population plummeted from an estimated 250,000 to 500,000 in 1492 to just 60,000 by 1508. Six years later, a census recorded 26,334. By 1542, only 2,000 remained. By 1802, official records declared them extinct. This pattern repeated across the Caribbean with mechanistic efficiency: a ninety per cent population decline within half a century, eventually contributing to what historians term “The Great Dying”—a hemispheric catastrophe that saw indigenous American populations crash from 54 to 61 million to a mere 6 million by 1700.

Disease played its lethal role, certainly. The 1518-1519 smallpox outbreak alone killed ninety per cent of survivors, whilst measles, typhus, and influenza ravaged populations lacking acquired immunity to Old World pathogens. Yet the comfortable narrative that attributes genocide primarily to “unintentional” disease spread—as though conquistadors were merely unfortunate disease vectors—absolves systematic violence that deserves no absolution.

Raphael Lemkin, who coined the term “genocide” in 1944, specifically cited Spanish treatment of indigenous Americans as a defining example. Historian Andrés Reséndez argues that “slavery has emerged as major killer,” with anthropologist Jason Hickel documenting that forced labour in mines and plantations killed one-third of indigenous workers every six months. The encomienda system—which “granted” Taínos to Spanish settlers as property—operated as institutionalised slavery by another name.

Direct violence was equally systematic. The 1503 Jaragua massacre on Hispaniola saw Spanish forces slaughter hundreds during a supposed peace gathering. Military campaigns targeted resistance movements with brutal efficiency. Sexual violence against indigenous women was so widespread it became demographically significant—a fact later confirmed through genetic analysis showing zero per cent Y-chromosome DNA but sixty-one per cent mitochondrial DNA amongst Puerto Ricans, evidence of unions between indigenous women and European or African men.

Perhaps most insidious was weaponised starvation. Spanish colonisers disrupted traditional agricultural systems, converting communal lands to plantation agriculture. Between 1495 and 1496, an induced famine killed 50,000 people on Hispaniola. Some Taíno communities refused to plant crops as resistance, choosing starvation over collaboration—a choice that speaks to desperation beyond modern comprehension.

Harvard historian Samuel Eliot Morison, writing in 1942, offered an assessment that remains definitive: “The cruel policy initiated by Columbus and pursued by his successors resulted in complete genocide.”

The Fiction of Extinction, The Reality of Survival

For two centuries, that genocide appeared complete. Colonial authorities had declared victory not merely through violence but through bureaucratic erasure. The 1787 Puerto Rican census listed 2,300 “pure” Indios. Fifteen years later, the number read zero. Not because these people had vanished, but because Spanish colonial administration found their continued existence inconvenient to land claims and labour systems that presumed indigenous absence.

This “paper genocide” succeeded so thoroughly that even mid-twentieth-century scholarship treated Taíno extinction as historical fact. Then came the DNA.

Martínez Cruzado’s 2003 study didn’t merely shock the scientific community—it resurrected a people. That sixty-one per cent of Puerto Ricans carry Taíno mitochondrial DNA meant millions of Caribbean inhabitants were walking around with indigenous ancestry they’d been taught didn’t exist. A 2018 study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences sequenced the genome of a thousand-year-old Taíno woman from the Bahamas, confirming that modern Puerto Ricans, Cubans, and Dominicans share close genetic relationships with pre-Columbian populations. Nuclear DNA analysis revealed ten to twenty per cent indigenous ancestry across Spanish-speaking Caribbean populations.

The genetic evidence vindicated what indigenous communities had insisted all along: they had never disappeared. Jíbaro communities in Puerto Rico’s mountainous interior had maintained Taíno practices through oral tradition, disguising indigenous spirituality within Catholic observance to escape persecution. Traditional cassava bread preparation, conuco farming techniques, and hundreds of herbal remedies persisted through generations who understood that survival sometimes requires invisibility.

Since the 1960s, a Taíno resurgence movement has gained momentum, particularly amongst Puerto Rican diaspora communities in the United States. The 1998 establishment of the United Confederation of Taíno People formalised networks of descendant organisations from Florida to California, representing thousands of members. Taíno culture now appears in Puerto Rican school curricula. The Smithsonian’s Caribbean Indigenous Legacies Project documents continuity rather than extinction. What colonisers sought to erase, DNA has helped reclaim.

The Exception That Proves the Persistence

If genetic evidence reveals hidden indigenous ancestry across millions of Caribbean inhabitants, the Kalinago people of Dominica represent visible, unbroken continuity. Between 3,000 and 3,400 Kalinago live in the Kalinago Territory, a 3,700-acre reserve established in 1903 on Dominica’s windward coast—the only surviving intact indigenous Caribbean community.

Their persistence came at tremendous cost. The 1930 Kalinago Uprising saw colonial authorities kill two people and imprison the chief, subsequently abolishing the chief position for twenty-two years. Only in 1978 did the Carib Reserve Act reaffirm land rights, followed by Dominica’s 2002 ratification of ILO Convention 169 on indigenous peoples. In 2015, the territory officially adopted the name “Kalinago,” reclaiming their self-designation over the colonial label “Carib.”

Today, twenty-six-year-old Chief Lorenzo Sanford—the youngest ever elected—leads a community navigating impossible contradictions. The Kalinago Territory remains among Dominica’s most economically marginalised regions, its poverty a direct legacy of colonial dispossession. Land is held communally, preventing individuals from using it as collateral for loans—a traditional system that protects against loss but inhibits economic development by Western metrics. Hurricane Maria’s 2017 devastation hit the territory particularly hard, its direct Atlantic exposure making it climatically vulnerable in an era of intensifying storms.

Kalinago artisans produce traditional baskets and crafts, participating in a tourism economy that simultaneously celebrates and commodifies their heritage. Few fluent speakers of the Kalinago language remain, making preservation efforts increasingly urgent. The community faces the perpetual tension between cultural continuity and economic survival, between maintaining traditions and adapting to contemporary realities.

The Unfinished Story

The persistence of Caribbean indigenous peoples raises uncomfortable questions that resist tidy resolution. What does it mean that millions carry indigenous DNA yet indigenous rights remain contested? How do we reconcile “extinct” peoples who are demonstrably alive? Why does the extinction narrative persist when genetic evidence proves otherwise?

The answers implicate ongoing colonialism more than historical ignorance. Declaring peoples extinct legitimises land claims and absolves present-day societies from obligations toward indigenous communities. Recognition requires redistribution—of resources, certainly, but also of historical narratives that flatter settler societies by portraying colonisation as regrettable but complete, rather than ongoing.

The Kalinago Territory’s poverty, the Taíno descendants discovering their heritage through DNA tests, the continued absence of federal recognition for Caribbean indigenous communities—these are not historical footnotes but present injustices. They reveal that genocide’s most enduring violence may be its insistence on completion, its demand that survivors remain invisible or cease to exist at all.

Yet survival itself constitutes resistance. Every Puerto Rican learning their mitochondrial DNA carries Taíno markers, every Kalinago artisan weaving traditional patterns, every researcher documenting linguistic persistence—they collectively unmake the colonial fiction of extinction. They insist that history is not finished, that identity remains fluid and contested, that peoples written out of official narratives can write themselves back in.

The Caribbean’s indigenous peoples never left. They simply refused, against overwhelming violence, to be erased. That refusal continues today, in DNA strands and woven baskets, in language fragments and land claims, in the stubborn fact of existence against a history that declared it impossible. The question now is whether the societies built atop their dispossession possess sufficient courage to recognise what never actually disappeared.